Blog

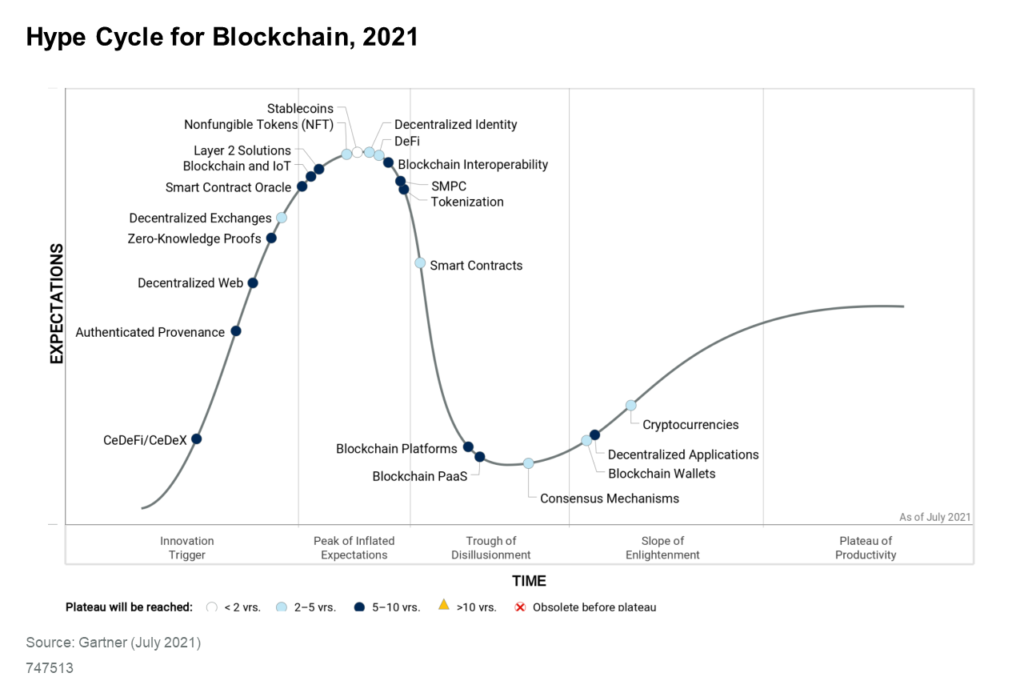

Web3, NFT, DAO, DeFi, CeFi, ETH, DOT, SOL, AVAX, FTM, blah…

It’s easy to blow off everything blockchain when the hype is so insane. That said, over the last 30 years I’ve been up close to some of the fastest growing businesses the planet has ever seen, and I’ve never seen this speed of innovation or adoption — directly tied to money, no less.

So what does all this mean for logistics? At its core, the world of blockchain is simply a way to build services that have no escrow agent. For example, Walmart is the escrow agent for all of Walmart’s inventory data. Obviously, they have no interest in sharing their inventory data with Amazon. But if Walmart and Amazon could use a 3rd party escrow agent, such as Deloitte, to access their inventory data and find ways for the two companies to lower costs by combining half full containers when they are transported, then both companies might get value out of that escrow agent. Blockchain begs the question: what if the blockchain was the escrow agent, and Deloitte was not needed? In other words, get rid of the escrow agent, but keep all the benefits of a third party verification service.

Where this gets more interesting is where the data flows accelerate, but trust is still an issue. For example, a manufacturer like Apple might want to access all the data from its suppliers’ ERP systems, so it can tighten up its supply chain. Again, a 3rd party could be brought in to mediate. But remember a supplier might have a thousand customers, and all thousand of them might want to access its data. Deloitte could build a massive data marketplace. Or maybe blockchain can offer a better solution.

Now fast forward to the “internet of things,” when every item in a warehouse is broadcasting its whereabouts. Nothing needs to be scanned any longer. Micro-fulfillment houses are everywhere, possibly even inside of your garage. Our biggest enemy is moving inventory needlessly. When the Q4 ramp-up ends, no one wants to be the one holding the leftover inventory. It sure would be nice to hedge against a bad Christmas season. Enter blockchain: our escrowless, financially-savvy network of inventory information, across multiple entities, allows something magical to start happening: manufacturers can lock in prices, just like grain and corn commodities do before tornado season, by buying and selling options against their inventory. A garage owner can store a small amount of non-perishable inventory, and Walmart can pay a premium for one item to be hand delivered two houses down, rather than ship the inventory from a central depot. That same garage owner can buy up options on Walmart’s local inventory, ensuring Walmart a guaranteed revenue through Christmas, while at the same time lowering open stock and driving up prices to sell its own small batch at a higher premium.

This is all to say, blockchain is following the “build it and they will come” mantra of design, which is usually a terrible approach. But the speed of blockchain innovation is so overwhelming that it is likely to stumble upon interesting new use cases through the formula of brute force x massive repetition = serendipity.

In short: I believe that young crypto addicts that spend evenings and weekends at hackathons can reinvent supply chains. Please visit my office hours and continue this conversation.

English Edition | Thai Edition | Russian Edition

“While it’s difficult to top Sander’s Pulitzer nomination and Schechter’s Stanford degrees, we must gladly admit that your book ROCKS!”

—Tom Peters Company

“The supply chain is corporate America’s last frontier. Conquering it is the key to reducing costs and maximizing profits. Damon Schechter and Gordon Sander have done a remarkable job of demonstrating the importance of supply chain management—to today’s business. They also show how the art of supply chain management evolved out of the military art of logistics, and how the most successful military leaders, from Alexander the Great forward, were, for the most part, successful supply chain managers as well. Great reading and a must for any forward-looking business executive’s library.”

—William “Gus” Pagonis, Senior Vice President of Supply Chain Management, Sears, Roebuck and Co., and Lieutenant General, U.S. Army (retired)

“Delivering the Goods is an important milestone in helping educate business executives in the importance of logistics. Schechter and Sander skillfully articulate both the historic and contemporary value of logistics, making the book a must-read for any executive looking to enhance customer satisfaction and reduce the cost of doing business.”

—Yossi Sheffi, Director, MIT Center for Transportation Studies, and recipient of the Distinguished Service Award, Council of Logistics Management

“With Delivering the Goods, Schechter and Sander have taken a previously neglected aspect of business and shown how supply chain management can transform an enterprise. Using examples from military history and modern industry, they show conclusively that sound logistics and their Tri-Level View can improve any organization’s bottom line.”

—David Kelley, Founder and CEO, IDEO Product Development, the creators of the Apple Mouse, and Professor, Stanford University Product Design program

“Logistics is the basis of strategy in the business world, as well as the military. In Delivering the Goods, the authors accord it the importance it deserves.”

—Sir John Keegan, bestselling author of The Face of Battle and A History of Warfare

“A fascinating history of logistics coupled with a pragmatic approach for turning your supply chain into a strategic differentiator. This is a great book to get marketers and supply chain leaders on the same page!”

—Ralph Drayer, former Chief Logistics Officer, Procter & Gamble

“Damon Schechter and Gordon Sander have made a valuable contribution to management thought. Their book, Delivering the Goods is exceptionally clear. Readers who had the benefit of learning logistics during their military service will appreciate the attention that this book provides. Other readers will benefit from their application of the Tri-Level View which the authors use to extend business logistics into supply chain management. The Tri-Level View is an interesting concept, one that is fresh.”

—Robert Delaney, author of the annual State of Logistics Report

“The book is terrific and fun to read. Damon Schechter and Gordon Sander discuss past business logistical practices of firms like Ford and Sears, and ask why so many firms today have not followed in their footsteps, given current market realities. The book is bound to enlighten all those looking for a better understanding of what it takes to compete and survive in today’s marketplace.”

—Robert Tamilia, Professor of Marketing, University of Quebec at Montreal

“Delivering the Goods is reminiscent of my entire 30 year career in logistics, from the military’s longtime mastery of the field, to the business world’s recent recognition of its strategic importance. This is the first book I have read which contains an insider’s perspective of both the military and business facets of this exciting field. It is an excellent primer for what is likely to be the most important field of business management during the coming decade.”

—John Kenny, Vice President of Logistics, 3Com Corp.

“Supply chain management has become the key differentiator for today’s competitive business world, and Delivering the Goods is one of the best books that I have read for conceptualizing this often misunderstood field. Schechter and Sander have refreshing viewpoints, drawing a particularly great analogy between military and business logistics.”

—Hokey Min, Executive Director, Logistics and Distribution Institute, U. of Louisville

“Effective, integrated supply chain management can and does generate enormous value for organisations, particularly those with global distribution needs. The authors creatively compare modern business cases with military-based logistics scenarios to demonstrate the need for supply chain efficiency and the importance of logistics for today’s managers.”

—John Allan, Chief Executive, Exel

“Damon Schechter and Gordon Sander have clearly illustrated the importance of logistics and supply chain management to business success. The historical context demonstrates how logistics and supply chain skills are both critical today just as they were in the past. In addition, the Tri-Level View provides managers a framework for better management.”

—Donald Rosenfield, Director, MIT Leaders for Manufacturing Fellows program, and author of Modern Logistics Management

“Damon Schechter and Gordon Sander get it…business is war! Companies like Wal-Mart, Procter & Gamble and Toyota have created tremendous shareholder value by embracing supply chain management as a competitive weapon. In Delivering the Good, the authors skillfully convey the elevation of logistics as a key differentiator on the battlefields of business based on the lessons of successful military campaigns.”

—John Lanigan, CEO, Logistics.com, and Commanding Officer of a Coast Guard Port Security Unit during Operation Desert Storm

“Damon Schechter and Gordon Sander bring a fresh approach to business logistics. Their tri-level model and analogies to military logistics ensure their book is far more insightful and interesting than a typical ‘how to’ tract.”

—Graham Sharman, Professor of Logistics and Supply Chain Management, Technical University of Eindhoven, The Netherlands

“Both as a consultant and a venture investor I have seen the critical importance of supply chain management in creating competitive advantage for the few who master it, as well as the disadvantage for the many who do not. Delivering the Goods is all about obtaining that advantage.”

—Geoffrey Moore, Venture Partner, Mohr Davidow Ventures, and bestselling author of Crossing the Chasm

“Damon Schechter and Gordon Sander have delivered a very readable and entertaining book that examines the importance of logistics in supply chain management. The examples are lively and comprehensive and the authors’ tracing of the development of logistics in the business enterprise is a fascinating and informative narration that makes “history come alive.” Overall, Delivering the Goods is a recommended read for those involved in the day-to-day practice of supply chain management.”

—James Stock, Professor of Marketing & Logistics, University of South Florida, and co-author of Strategic Logistics Management“Damon Schechter and Gordon Sander take the reader on a far ranging historical ride, highlighting the importance of logistics to military victory through the ages. What is the relevance of this to modern business? Critical, the authors argue, and provide insights and tools aimed at improving the performance of both public and private enterprises today.”

—Sheila Widnall, Abby Rockefeller Mauze Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics, MIT, and Secretary of the U.S. Air Force, 1993-1997

“Delivering the Goods uses historical perspectives and concise case examples to bring a much-needed clarity to the definition of logistics, while also presenting a compelling case for the value that can be gained by managers who improve logistics as a top business priority. The core tenets of this book represent the same values and business-results orientation that are key drivers of Ryder’s worldwide logistics and transportation solutions.”

—Gregory Swienton, CEO, Ryder System, Inc.

lo·gis·tics

/ləˈjistiks/

noun

• the detailed coordination of assets, business processed, and information to satisfy customer (or soldier) demand

• the forgotten second half of marketing: satisfying demand

The word logistics originally traces back to Greek origins. In Greek, λογῐστῐκός, or logistikós, relates to having skill in numerical calculations. Yet in the 19th century, French military officer and writer Antoine-Henri Jomini used the word logistique “to designate those who are in charge of the functionings of an army.”

In the 20th century, we saw both meanings come together full hog. First came the Industrial Revolution, which dramatically improved the capabilities of modern armies. Faster-firing weapons quickly outpaced the ability of troops to carry their supplies with them for an entire campaign, and we saw a shift to maintaining supplies in a rear area and transporting them to the front. The logistics of supplying troops became crucial in deciding the overall outcome of wars. Protecting one’s own supply lines and attacking those of an enemy became a fundamental military strategy.

Then from the logistics of WWII grew the field of operations research, as a way to apply mathematical models, statistical analysis, and mathematical optimization to a given set of resources. In war, and what was to become clear in business, logistics is about mathematically balancing a maximum objective (profit, performance or yield) and a minimum objective (loss, risk or cost), and improving this balance over time.

The business logistics wakeup call happened in 1962, when noted management expert Peter Drucker published an article in Fortune magazine titled “The Economy’s Dark Continent.” His thesis was that the hermetic, promotion-obsessed people who managed and directed the U.S. economy were, for all practical purposes, blind, by dint of their ignorance of and obliviousness to the logistic dimension of their jobs. Drucker noted that “almost 50 cents of each dollar the American consumer spends for goods goes for activities that occur after [my italics] the goods are made.” Distribution—or logistics, as it was then construed to mean—was half of the ball game. Nevertheless, the writer declared, in a much-quoted passage, “We know little more about distribution today than Napoleon’s contemporaries knew about the interior of Africa. We know it is there, and we know that it is big; and that is about all.”

The logistics function was spread out among such in-house departments as engineering, traffic, shipping, warehousing, and accounting. No one was in charge of the various functions and activities that came under its amorphous head. Management’s visibility of these processes—of this dark continent—was limited. Hence the CEO’s field of vision and ability to maximize profits was limited, and he couldn’t be a very good CEO, could he? Such was the essence of Drucker’s indictment.

A related problem, according to Drucker, was the difficulty of evaluating the cost of logistics.The varying nature and definition of the logistics function group, from company to company, combined with the lack of accurate or easy-to-use computational measuring tools made it difficult to find out how much these functions cost their respective companies, further blurring them. However, for Drucker, the basic reason for American business’ logistic obtuseness continued to be, essentially, a matter of attitude, that is, the perception, both within the factory walls and from without, that anything associated with logistics was unskilled or donkey work. Thus, Drucker charged, “because, to a technically minded man, most distribution work is donkey work, he tends to put a donkey in charge, more often than not a man of proven incompetence.”

To Drucker, the most blatant illustration of American business’ logistics obtuseness could be seen when one opened the door to the mercantile twilight zone known as the shipping department. “Even in the best-managed plant things change dramatically as soon as one goes through the door labeled ‘Finishing Room’ or ‘Shipping Department’ [where] there is suddenly a mob of people. Everybody seems to rush and no one seems to know why and where.” In short, all was pandemonium.

The only way to assert control of this messy, neglected process, Drucker insisted, was for businessmen to look at their business in a new holistic way—by seeing logistics, as an integral part of the manufacturing process, rather than a boring auxiliary of it, as was so often the case. “At a time when American business faces great competitive pressures from abroad—especially from a unified Europe whose industries can hold their own in technology, manufacturing knowledge, equipment and salesmanship,” he continued, sounding an almost eerily prescient note, “raising the effectiveness and cutting the costs of the American distributive system may be a more important and more urgent job than most managers yet realize.”

And so, by building upon the basic vision of modern American marketing, a vision based on seeing logistics as the reverse side of marketing—as well as a set of interrelated activities unto itself comprising transportation, warehousing, traffic, finished goods, inventory controls, packaging and materials handling—Drucker helped set the stage for and helped usher in the brave new world of what came to be called integrated logistics management, and the intellectual basis of what we today consider modern logistics.

In 1991, the Council of Logistics Management commissioned a study to determine the potential of applying logistics principles to service organizations, and as it turned out the principles of logistics were even more important in service organizations than in production firms. In a service organization, there may not be warehousing or inventory, but the fundamental coordination of assets, business processes, and information, to achieve maximum and minimum goals, remains the same.

Then the Gulf War and the Internet happened, accelerating an Information Revolution in logistics. The field of logistics has since become a free-for-all: WebVan, Kiva Robots, Shipwire, Fulfillment By Amazon, Instacart, Shopify Fulfillment, the UPS drone airline, and on the services side, Salesforce is the king of tools that help a business holistically satisfy the demands of its customers. Defining logistics as just warehousing and transportation of physical goods suddenly sounds quaint and naive.

In 2002, I published Delivering the Goods, and posed a question: can we view the entire world as one large warehouse? As it stands, there is a science to laying out and optimizing the operations inside the four walls of a warehouse. There are fixed costs, tradeoffs between cheap human labor and expensive, hard-to-upgrade automation, and information that can be used more and more intelligently. Given a range of inputs, it’s possible to rapidly AB test different iterations inside the warehouse, and incrementally improve the outputs indefinitely. Our three measures of success are faster, cheaper and better. If we throw out the competing notions of warehouse versus truck, can we more rapidly AB test different ways to satisfy demand?

In 1995, the U.S. Armed Forces asked a similar question: can a cargo plane also serve as a warehouse? And when it lands, can containers be offloaded that themselves operate as mini-warehouses, that can in turn be broken down into micro-warehouses at the pallet level and transported to the front? And then can we roll it all back up to the cargo plane-level at a later date? This was part of Gen. John Shalikashvili’s Joint Vision 2010. In this hierarchical scenario, where does the warehouse end and transportation begin? Fast forward to Travis Kalanick’s UberX, which is being copied by Amazon Flex to upend last mile delivery, and which Travis learned from to create CloudKitchens, which is using underutilized real estate in cities to enable restaurants to set up kitchens for the purpose of catering exclusively to customers ordering in. It’s as though Travis is being coached by Alexander the Great, running updated calculations of the load one man can carry, and then building forward supply depots to cross Asia—Travis’ key market for CloudKitchens is India.

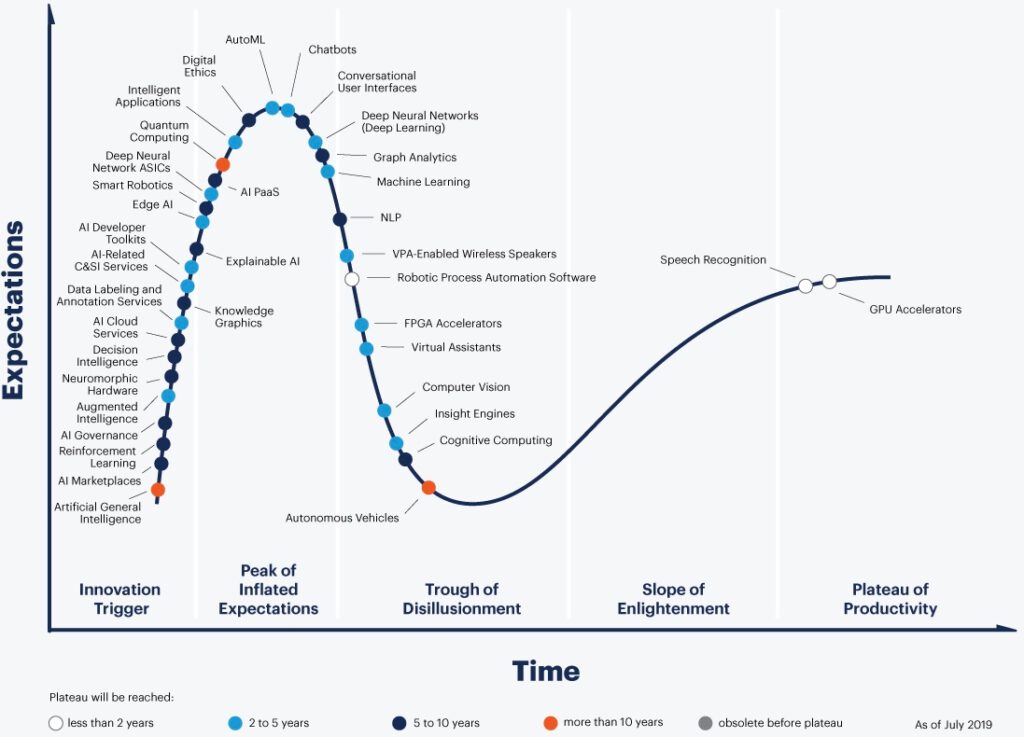

What logistics technologies are next in line to upend the way we satisfy demand? Autonomous vehicles, artificial intelligence, 3D printing, mobile distribution centers, unmanned kiosks, smart lockers, cloud-based workflow automation, augmented reality, telepresence, and more.

To sum it up, the first half of marketing is creating demand. Logistics is the forgotten second half of marketing: satisfying demand. Whether you sell a product or service, your Chief Logistics Officer is the person responsible for delivering the goods.

Click here to read more about the third logistics revolution.

Cross border commerce remains interesting because there is no big winner yet. Not Amazon. Not Alibaba. The reason is because doing commerce across a border is by its nature political, and hence local.

I’m reminded of a time eBay noticed a high density of orders between the U.S. and Germany. They setup a dedicated shuttle service between the two locations. They jumped through all the legal and logistical hoops to create a very specific, niche service, that was probably short-lived.

There are an endless supply of very specific, niche shuttle services that could be built profitably by entrepreneurs. Granted many will be short-lived, for various reasons, but profitable and worthwhile nonetheless.

I also expect to see more and more labor arbitrages. For example, labor is significantly cheaper in China. But again these opportunities can be short-lived. Witness the tariffs and Cold War with China.

At Shipwire, we found that after the 2008 market crash, the U.S. market largely died for our ecommerce sellers. But then the European market picked up, so we opened a UK warehouse. Then it dissipated. But Australia and Canada became hotbeds, so we opened up warehouses there. And then as they faded, the U.S. market came back. If we had bet our business on a single specific, niche market, e.g. buying those warehouses, we would have ultimately gone out of business. Instead, we counted on markets constantly changing, and our asset-light approach left us with little to tie us to a winnowing market, and few competitors that could keep up with our flexibility as the market zigged and zagged. Adapting to market weakness was one of our greatest strengths.

My challenge to all in the politically fraught blue ocean of cross border commerce is to limit yourself to specific, niche shuttle services and labor arbitrages that are achievable. But do so in a way that your efforts can quickly be adapted to new markets. Please visit my office hours and continue this conversation.

At Shipwire, we would often see businesses start on Kickstarter or Indiegogo, and then migrate into a dozen or more “off-kickstarter” sales channels: setting up their own shopping cart, listing inventory in the Amazon marketplace, eBay, Groupon, marketplaces in Europe and Asia, and then start attending trade shows to find wholesalers to move the product into retail stores. Hundreds and sometimes thousands of orders would come in from all directions each day. Our systems would then need to map all these orders to inventory sitting in various warehouses around the world, to pick, pack and ship each order as quickly as possible.

All this sounds a bit complex, but doable. But what happens when the closest warehouse to an end consumer is in Los Angeles, but only half his order is in stock in that warehouse. Do we ship the other half from inventory sitting in Pennsylvania, or do we ship the entire order from Penn, or do we wait until new inventory arrives in Los Angeles in 2-3 days, and upgrade the shipping speed to overnight at no charge in order to meet Amazon’s service levels? But then do we ship the first half from LA today, or wait until the order is full later this week?

And by the way, where should we instruct future inventory to go, to avoid this problem in the future? Should we move any existing inventory between warehouses, to avoid issues with a Groupon promotion scheduled to go out next week?

And now that we’re ready to ship the order, what box should we use? Would two small boxes be less expensive to ship than one big, bulky box? Wait, how much does the box itself cost? Wouldn’t the box be significantly cheaper in our Chicago warehouse, where we buy in bigger bulk? But then how would the box savings compare to the increased shipping costs from Chicago?

Oh, and how long has the inventory been sitting in Chicago, collecting dust and storage fees? Have we been counting these carrying costs in all our calculations across all our warehouses? Wouldn’t life be easier if we had fewer warehouses to carry inventory? But again, how does that compare to the savings from shipping from more local warehouses?

Now we just need to answer all these questions in a millisecond, because thousands of orders are backing up with their own set of questions that need to be answered.

Welcome to the world of artificial intelligence. The best run businesses I’ve seen are already running into dozens of algorithms that intelligently route orders in real time. It’s reasonable to expect each algorithm to become a business in and of itself, that can be AWS’d (turned into a web service for other businesses to use, as Amazon is increasingly doing).

At Shipwire, our first algorithm handled packaging configuration in real-time, combining package sizes, availability and costs, with shipping costs and times, in order to route orders to ideal warehouses, along with a packaging instruction.

Amazon Flex is a completely different type of algorithm that we’ll soon see become its own business. Amazon Flex is basically UberX in reverse, where regular folks sign up to handle deliveries in their area. Amazon’s algorithm here allows them to hire a driver at minimum wage to handle last mile delivery, undercutting what they would pay UPS to do the same thing. This only works where Amazon has a high density of shipments. When they open the service to non-Amazon shipments, the density will go even higher, making this service even more effective. Where Uber is having troubles making a profit with the UberX business model, Amazon Flex appears to be having better luck building density and profit potential.

Now all this is well and good progress. But China is advancing far faster than the U.S. in artificial intelligence, and may one day soon be able to weaponize logistics algorithms. We all need to run faster to build artificial intelligence that helps supply chains run faster, cheaper and better. Please visit my office hours and continue this conversation.

Hype Cycle for Artificial Intelligence

Source: Gartner