Blog

Seeing these photos reminds me of a story as told to me by Ivan Hofmann, a former Board member of mine, and a godfather of logistics. Ivan helped start RPS, which became Fedex Ground, and then went on to meet with the US Postmaster General to discuss working together on eCommerce initiatives. I’m imagining this went down like two mob bosses meeting at a diner in neutral territory. Ivan and his team offered to pay the USPS to deliver Fedex packages, to the very same customers they’re already visiting every day.

This so called “last mile delivery” was owned by USPS, who had the density and predictability to reach every home in America every day, in the most cost-efficient way possible. I say this with no sarcasm. They absolutely have the density and predictability to be the most cost-efficient. That doesn’t mean they are, just that they have the best opportunity to be. And frankly, the litter box of failed “last mile” startups is piled high with people who thought they could be more efficient than the USPS.

But I digress, because the rejection and explanation from the US Postmaster General points to a subtlety of last mile delivery that opens the door for us to work with future entrepreneurs on this very same problem set, for niche solutions that ARE incredibly profitable. For example, FedEx Express and UPS Ground ARE niche solutions that are incredibly profitable. Case and point: FedEx Express and Ground operations pick up and drop off packages separately, sometimes arriving at the same place within minutes of one another. FedEx has made a strategic decision not to integrate the two business units.

Last mile delivery is a complex problem, with lots of inter-related variables, that are constantly changing. As told to me, the US Postmaster General responded to Ivan’s offer with something to the effect of: “Do you know how many 25 cent envelopes we can fit in the same space as your $7 cubic foot box? Even if you give us $1 to deliver that shipment, we just need four envelopes to make the same money.” Clearly more complex than you might have thought at the beginning of this story, and even Fedex didn’t recognize the inter-related variables with which the USPS deals. Now overlay this with the constantly changing nature of the problem: 25 cent envelopes have nearly gone extinct, and UPS’ niche 5-10 day parcel service has become its bread and butter, with density driving efficiencies that today translate to 1-5 day parcel service, including Saturday and Sunday delivery. The US Postal Service’s financial problems and UPS’s opportunities are first and foremost related to the success of consumer technology, such as email and eCommerce.

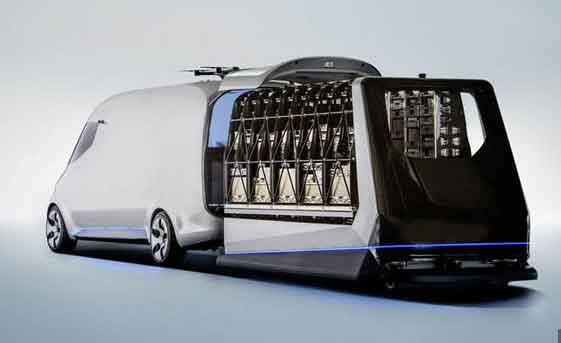

Now let’s turn to what Mercedes calls the Vision Van. A mobile warehouse concept. The German car and truck maker claims that the all-electric van can help boost the efficiency of delivery in urban areas by up to 50%.

The Vision Van comes complete with a fully automated cargo loading system and the ability to deploy delivery drones and self-driving robots to get parcels to customer doors quickly.

These new systems will allow delivery drivers to dispatch multiple packages at once, increasing efficiency, especially in urban environments.

The maximum load weight on the drones will be up to 4 pounds, which Mercedes says would cover around 85% of all Amazon delivery parcels.

These drones will also deliver their payloads to distances of up to 12 miles at speeds of up to 35 miles per hour, at heights of between 150 and 600 feet. This IS reinventing last mile delivery.

We’re not done yet. Let’s switch gears to look at Amazon’s Airborne Fulfillment Center (AFC), for which it was awarded a patent. Here’s a rough sketch of the idea:

The AFC is a blimp or airship that is capable of flying at altitudes of up to 45,000 feet and would store inventory that is delivered via drone to customers below.

In the patent, Amazon describes a method by which some type of aerial shuttle would fly into the airship’s storage area to deliver inventory and drones, while those staged drones later deliver items to a customer’s home, or maybe even to a seat at a football game.

For example, an attendee at a football game might want to order a meal or a jersey without ever leaving his or her seat. The system Amazon describes would potentially enable customers to receive those orders within minutes, though the idea of drones flying into stadiums is a bit hard to digest.

The core idea seems to be that airborne fulfillment centers could respond to surges in local demand even before they occur, according to the patent filing.

Large gatherings of people for a specific event, such as a concert or a sports game, are one example Amazon highlights as a clear-use case. But Amazon also appears to believe that using airships could reduce the costs of drone delivery in general.

One major problem with drones for ecommerce delivery is that they, for now and likely some period of years, will have pretty limited flying ranges. That means Amazon or others would need to build many, many additional fulfillment centers to get product close enough to customers to make drone delivery practical.

Since the drones that Amazon is testing can’t get up to heights anywhere near as high as 45,000 feet on their own, Amazon said in its filing that drones will fly back to a ground installation after delivering the order, where they’ll be placed in a shuttle and brought back to the AFC. The drones apparently can descend from those lofty heights by gliding down with little use of energy.

But what if the inventory could fly in an airship to get within drone delivery range? That possibility is also key to the thinking behind Amazon’s airborne fulfillment center concept.

The Amazon filing noted that “The use of an AFC and shuttles also provides another benefit in that the AFC can remain airborne for extended periods of time. In addition, because the AFC is airborne, it is not limited to a fixed location like a traditional ground based materials handling facility. In contrast, it can navigate to different areas depending on a variety of factors, such as weather, expected demand, and/or actual demand.”

Can it work? There would seem to be a number of obstacles, such as how does Amazon get drones back into the aerial shuttle after they make deliveries? But it’s another interesting concept from Amazon, and just the latest in a never ending series of innovative ideas.

In what situations would the AFC be ideal? I’m thinking military applications are a good place to experiment. Where won’t they work? I’m guessing urban cities don’t need a drone invasion added to their list of problems right now.

And where would the Vision Van be ideal? And where won’t they work? Are there hybrid versions of these two ideas you think would work for specific use cases? If so, let us know, and we can help you run a quick test.

Or do you have an entirely new idea for a mobile distribution center that has nothing to do with drones? For inspiration, check out this 1992 article about Wolfmobiles delivering hot dogs to the to troops on the Gulf War battlefield. Product fit is the hard part here. Let’s start with flushing out the use cases, and build product specifically for them. Please visit my office hours and continue this conversation.

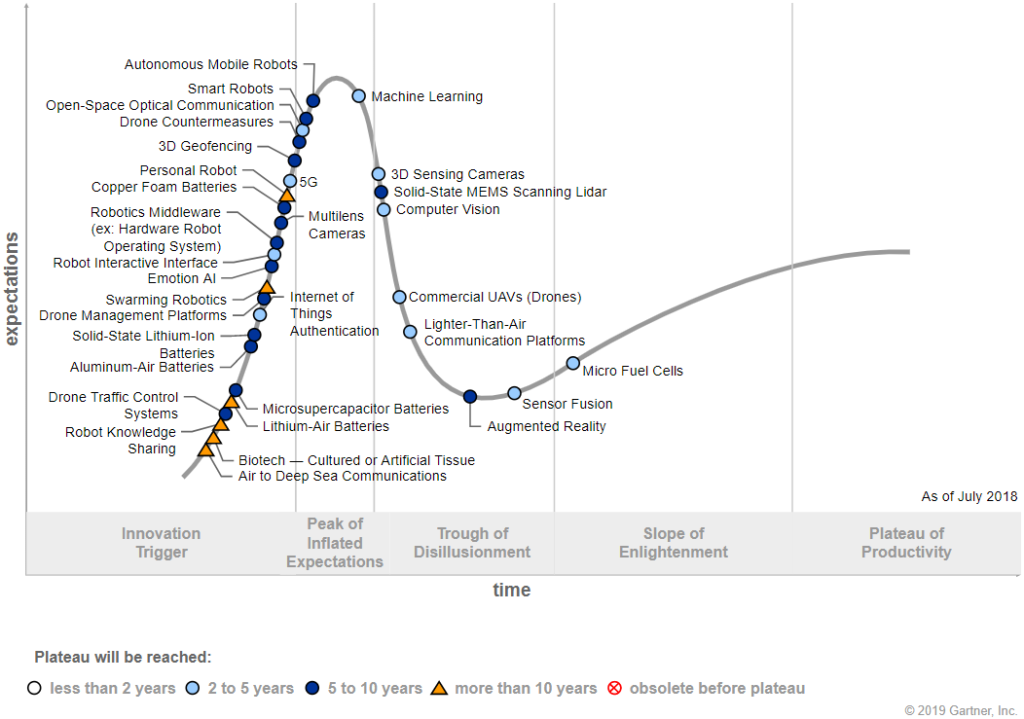

Hype Cycle for Drones and Autonomous Robots

Afterthought

Uber found Travis Kalanick is making a big foray with CloudKitchens, which enables restaurants to set up kitchens for the purposes of catering exclusively to customers ordering in, as that’s how many people are consuming restaurant food in increasing numbers. The kitchens are established in underutilized real estate that Kalanick is snapping up through a holding company called City Storage Systems. In the same vein that we are discussing mobile distribution centers, we should also be considering forward supply depots like CloudKitchen. Regardless of how well you think this model would work in your neighborhood, consider the global applications, such as in India where they are having the fastest traction.

Excerpt from Delivering the Goods: The Art of Managing Your Supply Chain (Wiley, 2002)

Before moving ahead with any action plan, you need to identify the key risks of moving ahead. These are some questions for your contingency planning, your reality test: What do you do in the event of budget problems or scheduling problems? What do you do in case of an earthquake or attack by terrorists? Unfortunately, as we saw on September 11, 2001, they are a part of reality, too.

Ask yourself: How intelligent are your policies and procedures you have in place in the event of a sudden breakdown in your supply chain? Having all the members of a team hop on a plane to meet face-to-face is nice from a theoretical point of view, but not very realistic. With less and less face time, organizations need to cooperate and adapt their policies and procedures to this new virtual, less personal world.

Gus Pagonis, the genius of the Gulf War, who crossed the military/civilian divide and now runs the logistics of Sears, Roebuck, and who is one of the role models for this book, is a strong believer in teleconferencing—with a caveat. He warns that “if you had an inefficient meeting before, it’s really going to be disastrous if you try to do it telecommunicating. So I think that the whole business world is in for a huge wakeup call.” Translation: Better technology doesn’t necessarily make for a better meeting. First, the minds who go into that meeting have to give some considered thought to what they want to accomplish in that meeting, or else the result will simply be televised bedlam. Mixed-up minds will make for a mixed-up meeting, whether it is televised or not. This means that all of the members of your logistical team have to know your company’s logistics, including your fallback system incase of a September 11 or similar disruption before the emergency takes place.

What are your contingency plans in the event of an all out disaster? On the morning of September 11, after the first plane had hit the World Trade Center, and even before the second plane hit 18 minutes later, General Pagonis quickly activated his contingency operations center at Sears. Consequently, Pagonis knew and was able to tell his CEO and commanding officer where all of the company’s trucks were at that point in time, which ones were stranded, which couldn’t get through customs, where his containers were, which stores were closed, what malls were closed, what tunnels were closed, and so on and so forth.

Having practiced for such a contingency on numerous occasions, as well as having the operations to deal with it in place, Pagonis and his corporate logistics team were ready to switch into lockdown mode at a moment’s notice. Consequently, there was no breakdown in the Sears supply chain at all. Although Pagonis’s team had to go to 24/7 mode, as did similar logistics teams at corporations around the country, Sears suffered virtually no logistical problems at all. Even with FedEx grounded for three days, Pagonis and his team were still able to deliver the goods.

How well did your company respond to September 11? How good are your contingency plans? Are you as prepared as Sears was for a sudden disruption to your supply chain?

Excerpt from Delivering the Goods: The Art of Managing Your Supply Chain (Wiley, 2002)

In 1962 management expert Peter Drucker published a landmark article about business logistics, or distribution as it was then called, in Fortune magazine. It was Drucker’s thesis that the hermetic, promotion-obsessed people who managed and directed the U.S. economy were, for all practical purposes, blind, by dint of their ignorance of and obliviousness to the logistic dimension of their jobs. Drucker noted that “almost 50 cents of each dollar the American consumer spends for goods goes for activities that occur after [my italics] the goods are made.” Distribution—or logistics, as it was then construed to mean—was half of the ball game.

Nevertheless, the writer declared, in a much-quoted passage, “We know little more about distribution today than Napoleon’s contemporaries knew about the interior of Africa. We know it is there, and we know that it is big; and that is about all.” To back his charges of logistic absent-mindedness, Drucker cited a recent NYU survey of 28 putatively modern firms and what functions and business activities their CEOs considered important or significant.

Fewer than half of the polled executives admitted to giving distribution or logistics any significant attention.

As a result, Drucker asserted, appearances to the contrary, the U.S. economy was not realizing its full potential.

According to Drucker, few companies think of their distributors when they speak of “their business.” “Their [limited] horizons are set by the legal boundaries of their corporation.”To cite one of the more glaring manifestations of corporate America logistic short-sightedness, Drucker observed that few firms either knew how large their distributors’ inventories were, or, apparently, cared. The result was, well, nearly as portentous as the Dot.Com Bubble: “This [logistic] ignorance is a major cause of the persistent inventory booms and inventory busts that beset our economy.”

Not to mention millions of dollars of lost sales from undiscovered or dissatisfied customers.

One of the problems, he noted was the vague and amorphous way by which distribution was defined, with the distributive function spread out among such in-house departments as engineering, traffic, shipping, warehousing, and accounting; not to mention the distributive function assigned to the distributors themselves. With distribution dispersed, and no one in charge of the various functions and activities that came under its amorphous head, management’s visibility of these processes—of this dark continent—was limited. Hence the CEO’s field of vision and ability to maximize profits was limited, and he couldn’t be a very good CEO, could he? Such was the essence of Drucker’s indictment.

A related problem, according to Drucker, was the difficulty of evaluating the cost of distribution. The varying nature and definition of the logistics function group, from company to company, combined with the lack of accurate or easy-to-use computational measuring tools made it difficult to find out how much these functions cost their respective companies, further blurring them.

However, for Drucker, the basic reason for American business’s logistic obtuseness continued to be, essentially, a matter of attitude, that is, the perception, both within the factory walls and from without, that anything associated with logistics—or shipping, as this complex function group was then commonly referred to—was unskilled or donkey work. Thus, Drucker charged, “because, to a technically minded man, most distribution work is donkey work, he tends to put a donkey in charge, more often than not a man of proven incompetence.”

To be sure, Drucker noted, there were exceptions to this disheartening rule. At Sears, he noted approvingly, “every buyer is expected to know as much about the making of the product—the manufacturer, his plant, his process, his materials, his people, and his costs—as he knows about selling it in Sears stores.” But that—which was still Sears, Roebuck—was only one logistic point of light, as it were.

To Drucker, the most blatant illustration of American business’s logistics obtuseness could be seen when one opened the door to the mercantile twilight zone known as the shipping department. “Even in the best-managed plant things change dramatically as soon as one goes through the door labeled ‘Finishing Room’ or ‘Shipping Department’ [where] there is suddenly a mobof people. Everybody seems to rush and no one seems to know why and where.” In short, all was pandemonium.—As indeed, I was to find during my own explorations of the dark continent three decades later.

Who knew what waste and evil lurked in the heart of the average American manufacturing firm (to paraphrase the old radio serial, “The Shadow”)?

Peter Drucker knew. And now, the readers of Fortune did, too.

The only way to assert control of this messy, neglected process, Drucker insisted, echoing the logistic visionaries of the earlier part of the century, was for businessmen to look at their business in a new holistic way—by seeing distribution, or logistics, as an integral part of the manufacturing process, rather than a boring auxiliary of it, as was so often the case.

“At a time when American business faces great competitive pressures from abroad—especially from a unified Europe whose industries can hold their own in technology, manufacturing knowledge, equipment and salesmanship,” he continued, sounding an almost eerily prescient note, “raising the effectiveness and cutting the costs of the American distributive system may be a more important and more urgent job than most managers yet realize.”

And so, by building upon the basic vision of modern American marketing set forth by Archie Shaw in 1916, a vision based on seeing distribution as the reverse side of marketing—as well as a set of interrelatedactivities unto itself comprising transportation, warehousing, traffic, finished goods, inventory controls, packaging and materials handling—Drucker helped set the stage for and helped usher in the brave new world of what came to be called integratedlogistics management, and the intellectual basis of what we today consider modern logistics.

“Within the last few years,” said Drucker, ending on a more optimistic note than the Cassandra-like Reese, and noting the rapidly accelerating and improving state of logistic thought, “people have gained both the [logistical] perception and the tools to see the job. They have gained the perception to see systems which essentially people did not have 30 years ago, or even 20 years ago.”

To be sure, Drucker’s optimism about the future of distribution was well-founded, at least in part. Galvanized by his incisive analysis—as well as empowered by the new data-processing technology, which arrived in the latter part of the 1960s and which allowed them to quantify and cost their formerly “wild” (i.e., distributive) side—an increasing number of American business managers became disciples of Drucker. The onset of systems analysis helped further the idea that trade-offs between distribution activities could be achieved, which would lower operating costs without necessarily sacrificing product availability. Logistics was a funny art managers found. For example, they discovered, lower distribution costs could often be achieved via the most palpably expensive method—air freight, rather than by truck or rail. Perhaps there was more to this logistics thing than met the eye, after all . . .

Nonetheless, because of the persistence of the sales-fixated marketing philosophy and mentality, both within industry and in leading U.S. business schools—a problem that now two generations of business writers had identified and criticized—sadly, such logistically enlightened firms continued to be in the minority.

The root problem behind this nasty recrudescence of antilogisticianism (to coin an expression) during the 1960s—as it had proven during the 1920s, which mirrored that decade in its optimism and perception of the world as an ever-expanding universe with America at its center—was, one could say, the spirit of the Swinging Sixties itself, which, in its own memorable way, was as frothy and as superficial as was the age of Babbitt, the original, slogan-touting salesman conjured up by Sinclair Lewis in his famed 1927 novel of the same name. In the 1960s, Babbitt had morphed into the Man in the Grey Flannel Suit, as the equally famous novel about the archetypal, postwar—and, in this case, heroic—advertising man was called. In the booming, consumer goods-happy 1950s and 1960s Madison Avenue ruled.

In the world of American manufacturing this spirit translated itself into a continuing focus on sales, sales, sales. Like the 1920s, the 1960s were a fertile time for slick advertising campaigns and catchy jingles, some of which remain embedded in the American consciousness. Perhaps you remember some of them: “See the USA in a Chevrolet!” (Chevrolet); “Better Living Through Chemistry” (Dupont); “Mmm Good!” (Campbell’s Soup); and so forth. Unsurprisingly, some of the most memorable jingles were associated with soft drinks: “Things Go Better With Coke” (Coca-Cola); “You Like It It Likes You” (7 Up); and so forth. Most of them have never been topped.

All well and good. Some of these products became brand names on the strength and resonance of these phrases. However, they didn’t do much to promote sound business thinking or practice, and they certainlydidn’t do much to promote or enhance either the intrafirm or extra firm image or popularity of logistics or logisticians, who continued to remain in the shadow, and, more often than not, in the charge of their sales-obsessed, jingleminded managerial overlords and colleagues.

Alas, there was nothing sexy about either the idea or even the sound of logistics; just the opposite. Do you remember any brilliant ad campaign of the 1960s mentioning anything about reliable delivery?

And so, to paraphrase Rodney Dangerfield, logistics continued to get no respect.

This disrespect for logistics in the civilian sector corresponded with a similar attitude in the military one. Witness the difficulty that Joe Heiser, the Army’s top logistician during the Vietnam War had in Vietnam in getting respect from his immediate commander, who preferred a “fighting man” for his front-line logistics post, rather than a veteran logistician.

And so, as in the equally logistically retarded Army, and despite the manifest value and pivotal importance of logistics to the whole corporate battlefield, business logistics continued to be seen as the domain of the Shipping Room Mob, as Drucker put it. And so the big disconnect, as I call it, namely, the resistance of mainstream marketing thinking to sound, integrated logistics, and the subsequent gap between logistical thought and practice continued.

As a recent dissertation on the history of the evolution of logistics noted, this gap, bolstered by the perception that distribution work was “too applied and trade-schoolish to be part of the science and art of marketing,” would continue for at least another twenty years. Indeed, as I saw during my studies at Stanford University, where, even at that enlightened campus, logistics was relegated to a dusty corner of the Industrial Engineering curriculum, that gap would continue well into the 1990s.

Excerpt from Delivering the Goods: The Art of Managing Your Supply Chain (Wiley, 2002)

David Kelley, the famed founder of IDEO,America’s largest design and development firm, also heads the product design program at Stanford University. With a reputation as one of the most innovative designers and creative thinkers around today, Kelley seeks to nurture in his students the importance of knowing the customer.

Each year, on the first day of his most popular class, Human Values in Design, Kelley strides into the room carrying two bulging suitcases. For two hours, like a mad door-to-door salesman, he then proceeds to pull out one apparently handy gadget or contraption after another.

The only problem is, as Kelley effectively demonstrates to his laughing students, that none of these products really are actually handy. In fact, most of them don’t even work. A few—like a sexy, straight-from-the-factory can opener that, he shows, is guaranteed to slice your thumb off—are downright dangerous. It doesn’t take long to get Kelley’s point—that in their arrogance or stupidity, the designer and manufacturers of these absurd and even dangerous products have brought them to the market without properly testing them for either their safety or their desirability.

Thus, Kelley effectively demonstrates that if the age-old truth about necessity being the mother of invention—particularly worthwhile and profitable inventions—is still ever true, so is its obverse: that the absence of necessity, or customer need, can lead to some real lemons. Kelley’s corollary, you might call it.

Recently the efficacy of Kelley’s corollary was dramatically driven home in the larger, real world just beyond Stanford’s walls, amidst the hi-tech hills and dales of nearby Silicon Valley, when dozens of Internet start-up companies, including numerous once highly touted ones, went belly up. Why? Because, in the vast majority of cases, these misguided companies had plunged into designing, building, and implementing their sexy, cool, computer-based services while presuming that Joe Q. Public was interested in these services in the first place—or even, in some particularly obtuse cases, without even seeing whether the technology for delivering them to Joe and his family actually worked.

A recent and quite spectacular proof of Kelley’s rule—you could call it the look-before-you-leap-into-the-market rule—was provided by the catastrophic burnout of boo.com, the much-ballyhooed, London-based Net shopping service that reportedly went through more than $120 million before flaming out. When they started out in 1998, the young Swedish founders of boo.com, Kajsa Leander and Ernst Malmsten, had ambitions of being the upscale, readymade cyber-clothier to the world. Flush with start-up capital and cocksure of themselves, the two high-flying founders speedily hired a worldwide staff of about three hundred and established satellite offices around the United States and Europe. Photos of the ultraglamorous cyber-entrepreneurs appeared in magazines and newspapers around the world.

Alas, both Leander and Malmsten were so certain of themselves that they had not bothered to ascertain whether the average high-street shopper really wanted to buy his or her clothing off the Net—some did, most didn’t—or even whether boo.com’s much-vaunted, multifaceted, but, ultimately, hopelessly clumsy cyber-rack even worked.

It did not, and neither did boo.com. In May, 2000, less than two years after its bubbly take off, boo.com and its high living founders returned to Planet Earth—with a devastating thud, as the entire staff was fired en masse and the founders beat a hasty retreat.

Why? In Kelley-esque terms, Leander and Malmsten had, for all practical purposes devised a big can opener that didn’t work.

Common sense? Perhaps. But many—far too many—supposedly cutting-edge manufacturing and services companies lack fundamental common sense in the way they design, plan, market, and manufacture things. And, far too many overlook perhaps the most important aspect of their product or service: ensuring that it can be delivered accurately, on-time, and in the right quantity.

Perhaps Leander and Malmsten should have taken a class with David Kelley. If so, they would have learned that to be a designer—a successful designer—it is imperative to think and act like a person, a real person. They might have paid more attention to the unglamorous but very real need and desire on the part of their potential customers for their product to be delivered accurately, on time, and in the right quantity, something that they obviously ignored, as did many other of their fellow failed dot-commers. The lesson that Kelley inculcates in his students is that no matter how brilliant you think your product or design is, it’s best to consider it from every possible human perspective—including the delivery perspective—before going public with it.

Excerpt from Delivering the Goods: The Art of Managing Your Supply Chain (Wiley, 2002)

Logistics has only recently begun to receive the respect and recognition both it and logisticians deserve.

One reason it has take so long for American industry to get with it, logistically, is that much of the growing body of reliable and usable knowledge about logistics isboring, and difficult to understand. My new book, Delivering the Goods, hopefully rectifies this problem by showing how the story of the development and growth of American business logistics is the story of American business itself.

Perhaps the best place to begin our selective history of business logistics and logistical thought is with the tale of one of the first, and arguably, the most spectacular business failure in modern history: the South Sea Bubble.

The South Sea Bubble—which, like many “bubbles,” including the recent much-discussed dot.com bubble, was attributable to a combination of logistical ignorance, hubris, and downright fraud—is the name history has given to the apocalyptic failure of the world’s first great international trading company and wholesaler, the South Sea Trading Company. Founded by Robert Harley, an enterprising London businessman, the company gained immediate fame when, in 1711, Harley and his partners managed to persuade the British government, then deeply in debt, to give them a monopoly over certain of Britain’s lucrative trade routes with South America and the South Sea Islands. In return, the new trading company agreed to assume the bulk of that debt, which then stood at more than £10 million, in addition to an annual payment to the Crown of £600,000.

Thus blessed, the chartered company, and its small fleet of ships, became the leading provisioner to England of the diverse South Sea spices, South American fruit and tobacco, and all sorts of other exotic—and expensive—stuff. In this way, it also became, one could say, the world’s first brand name. The hype surrounding the South Sea Trading Company grew even bigger in 1718 when the sovereign himself, King George I, became its governor, creating yet new confidence in the enterprise, which yielded its initial investors massive returns reminiscent of the heady early days of the dot.com bubble.

The American colonists fell under the company’s magic spell just as readily as did their fellow subjects back home in England.

The South Sea Company was the company. If you were a Boston or New York merchant and placed an order with it, you could rely on it delivering the goods on time, give or take a week or two, allowing for the moods of the seas. Somewhere in the middle of the growing bubble of misinformation and hype around the company, there was, in fact, a company.

With that sort of reputation, in addition to the very conspicuous sight of the company’s original directors reveling in their newfound lucre, other investors soon became interested in getting in on what seemed like a sure thing. In 1719, eight years after the company was chartered, they got their chance when His Majesty’s government approved a further agreement under which the government’s creditors could exchange their claims on the Crown in return for stock in the by now famous firm. A swarm of such creditors rushed to buy stock. They were joined by a large number of ordinary citizens in Britain and the American colonies who also decided to invest, thereby pushing the value of South Sea stock from £128.5 to £1,000 in a matter of months. The gold rush was on.

Unfortunately, it was a fool’s gold rush, for these hapless investors were, by now, largely banking on a phantom. Unbeknownst to the public, as a result of a combination of bad seas, poor communications, and a generous helping of mismanagement and malfeasance, the company’s once relatively reliable system for the purchase and delivery of its cornucopia of goods had utterly broken down. By the time anyone realized the extent of the logistical bad information bubble, which had now fed into the speculative bad information bubble, it was too late to do anything about it. Meanwhile, Harley and his friends took a powder.

Of course, if the S.S.T.C. had had a few modern-day logistical troubleshooters in its employ, and the British government, which had chartered the company, had had a proper stock control apparatus, the ensuing South Sea Bubble, as it became known, could have been avoided. A telegraph system might also have helped. But this was still the early eighteenth century. Telegraph would not arrive until the nineteenth. Buyers and suppliers on both sides of the Atlantic, blithely unaware of the logistical rot at the heart of the company, as well as the increasing corruption surrounding it, continued to place their orders with the company, and purchased stock in it. And so the bubble grew and grew.

The fledgling London press, then at the start of its scandal-mongering days, eagerly rushed into the information breach, and reported the true state of the company’s affairs. Although some of the company’s original investors, as well as a number of corrupt government ministers, managed to enrich themselves, most wound up losing their investments. Many were left in ruins; some committed suicide. In the wake of the burst bubble, the House of Commons was forced to convene an official court of inquiry into the sordid affair. Its scathing report, issued in 1721, attributed the fiasco to a combination of greed, gullibility—and bad information. The South Sea Company itself, which continued to sail the seas until the mid-nineteenth century, was allowed to retain its charter, but only after completely revising its way of operating—including its logistical reporting procedures. However, the system, as well as the idea, of having chartered companies had been gravely weakened. The international business world had had its first great scandal, and logistics was at the heart of it.