Seeing these photos reminds me of a story as told to me by Ivan Hofmann, a former Board member of mine, and a godfather of logistics. Ivan helped start RPS, which became Fedex Ground, and then went on to meet with the US Postmaster General to discuss working together on eCommerce initiatives. I’m imagining this went down like two mob bosses meeting at a diner in neutral territory. Ivan and his team offered to pay the USPS to deliver Fedex packages, to the very same customers they’re already visiting every day.

This so called “last mile delivery” was owned by USPS, who had the density and predictability to reach every home in America every day, in the most cost-efficient way possible. I say this with no sarcasm. They absolutely have the density and predictability to be the most cost-efficient. That doesn’t mean they are, just that they have the best opportunity to be. And frankly, the litter box of failed “last mile” startups is piled high with people who thought they could be more efficient than the USPS.

But I digress, because the rejection and explanation from the US Postmaster General points to a subtlety of last mile delivery that opens the door for us to work with future entrepreneurs on this very same problem set, for niche solutions that ARE incredibly profitable. For example, FedEx Express and UPS Ground ARE niche solutions that are incredibly profitable. Case and point: FedEx Express and Ground operations pick up and drop off packages separately, sometimes arriving at the same place within minutes of one another. FedEx has made a strategic decision not to integrate the two business units.

Last mile delivery is a complex problem, with lots of inter-related variables, that are constantly changing. As told to me, the US Postmaster General responded to Ivan’s offer with something to the effect of: “Do you know how many 25 cent envelopes we can fit in the same space as your $7 cubic foot box? Even if you give us $1 to deliver that shipment, we just need four envelopes to make the same money.” Clearly more complex than you might have thought at the beginning of this story, and even Fedex didn’t recognize the inter-related variables with which the USPS deals. Now overlay this with the constantly changing nature of the problem: 25 cent envelopes have nearly gone extinct, and UPS’ niche 5-10 day parcel service has become its bread and butter, with density driving efficiencies that today translate to 1-5 day parcel service, including Saturday and Sunday delivery. The US Postal Service’s financial problems and UPS’s opportunities are first and foremost related to the success of consumer technology, such as email and eCommerce.

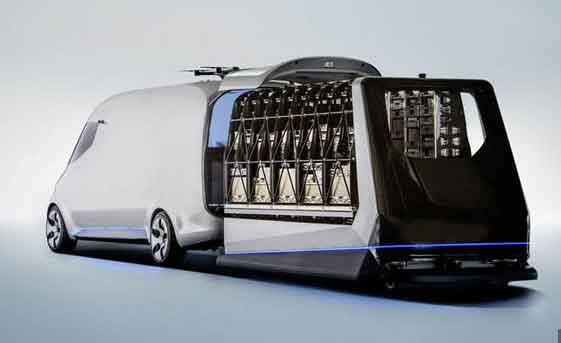

Now let’s turn to what Mercedes calls the Vision Van. A mobile warehouse concept. The German car and truck maker claims that the all-electric van can help boost the efficiency of delivery in urban areas by up to 50%.

The Vision Van comes complete with a fully automated cargo loading system and the ability to deploy delivery drones and self-driving robots to get parcels to customer doors quickly.

These new systems will allow delivery drivers to dispatch multiple packages at once, increasing efficiency, especially in urban environments.

The maximum load weight on the drones will be up to 4 pounds, which Mercedes says would cover around 85% of all Amazon delivery parcels.

These drones will also deliver their payloads to distances of up to 12 miles at speeds of up to 35 miles per hour, at heights of between 150 and 600 feet. This IS reinventing last mile delivery.

We’re not done yet. Let’s switch gears to look at Amazon’s Airborne Fulfillment Center (AFC), for which it was awarded a patent. Here’s a rough sketch of the idea:

The AFC is a blimp or airship that is capable of flying at altitudes of up to 45,000 feet and would store inventory that is delivered via drone to customers below.

In the patent, Amazon describes a method by which some type of aerial shuttle would fly into the airship’s storage area to deliver inventory and drones, while those staged drones later deliver items to a customer’s home, or maybe even to a seat at a football game.

For example, an attendee at a football game might want to order a meal or a jersey without ever leaving his or her seat. The system Amazon describes would potentially enable customers to receive those orders within minutes, though the idea of drones flying into stadiums is a bit hard to digest.

The core idea seems to be that airborne fulfillment centers could respond to surges in local demand even before they occur, according to the patent filing.

Large gatherings of people for a specific event, such as a concert or a sports game, are one example Amazon highlights as a clear-use case. But Amazon also appears to believe that using airships could reduce the costs of drone delivery in general.

One major problem with drones for ecommerce delivery is that they, for now and likely some period of years, will have pretty limited flying ranges. That means Amazon or others would need to build many, many additional fulfillment centers to get product close enough to customers to make drone delivery practical.

Since the drones that Amazon is testing can’t get up to heights anywhere near as high as 45,000 feet on their own, Amazon said in its filing that drones will fly back to a ground installation after delivering the order, where they’ll be placed in a shuttle and brought back to the AFC. The drones apparently can descend from those lofty heights by gliding down with little use of energy.

But what if the inventory could fly in an airship to get within drone delivery range? That possibility is also key to the thinking behind Amazon’s airborne fulfillment center concept.

The Amazon filing noted that “The use of an AFC and shuttles also provides another benefit in that the AFC can remain airborne for extended periods of time. In addition, because the AFC is airborne, it is not limited to a fixed location like a traditional ground based materials handling facility. In contrast, it can navigate to different areas depending on a variety of factors, such as weather, expected demand, and/or actual demand.”

Can it work? There would seem to be a number of obstacles, such as how does Amazon get drones back into the aerial shuttle after they make deliveries? But it’s another interesting concept from Amazon, and just the latest in a never ending series of innovative ideas.

In what situations would the AFC be ideal? I’m thinking military applications are a good place to experiment. Where won’t they work? I’m guessing urban cities don’t need a drone invasion added to their list of problems right now.

And where would the Vision Van be ideal? And where won’t they work? Are there hybrid versions of these two ideas you think would work for specific use cases? If so, let us know, and we can help you run a quick test.

Or do you have an entirely new idea for a mobile distribution center that has nothing to do with drones? For inspiration, check out this 1992 article about Wolfmobiles delivering hot dogs to the to troops on the Gulf War battlefield. Product fit is the hard part here. Let’s start with flushing out the use cases, and build product specifically for them. Please visit my office hours and continue this conversation.

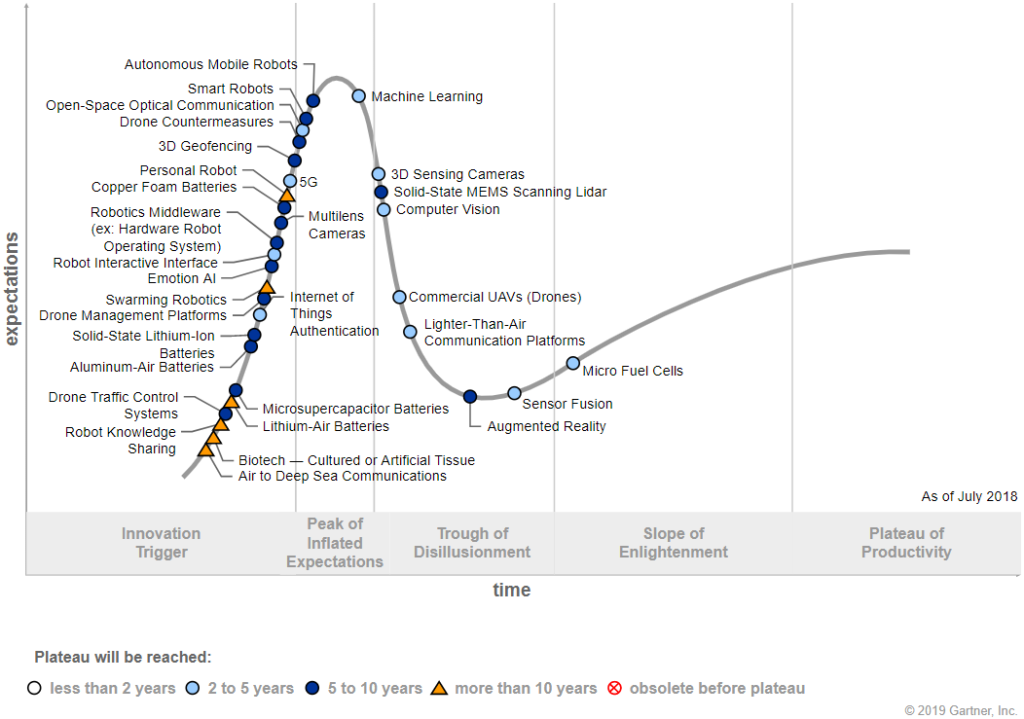

Hype Cycle for Drones and Autonomous Robots

Afterthought

Uber found Travis Kalanick is making a big foray with CloudKitchens, which enables restaurants to set up kitchens for the purposes of catering exclusively to customers ordering in, as that’s how many people are consuming restaurant food in increasing numbers. The kitchens are established in underutilized real estate that Kalanick is snapping up through a holding company called City Storage Systems. In the same vein that we are discussing mobile distribution centers, we should also be considering forward supply depots like CloudKitchen. Regardless of how well you think this model would work in your neighborhood, consider the global applications, such as in India where they are having the fastest traction.